MPSparse: GPU-accelerated Sparse Matrix Solvers, Part I

Source Code: The project referenced in this post, MPSparse, is available on GitHub.

MPSparse is a collection of GPU-accelerated sparse matrix solvers for Apple Silicon, written mostly in the Metal Shading Language (MSL), which is Apple's version of CUDA C++ for its M-series chips, and C++.

I've been working on this project with my friend Harry (highly recommend you to check out his website!) over break, and it's been an interesting experience.

The end goal is to eventually write an efficient direct solver for sparse matrices for Apple Silicon. Currently, the M-chips have GPU's, but they lag behind Nvidia's GPU's in terms of their respective systems; Nvidia has cuSPARSE for their GPU's, but Apple doesn't have anything, it only has the Accelerate framework, which is pretty good, but it runs on the CPU. The goal of this project is to build something

similar to cuSPARSE. At the time of writing this blog, we've written CGD and BiCGSTAB solvers for the CSR and BCSR formats.

Introduction

Apple's current solution isSparseSOLVER on Accelerate. This, however, leaves the massive parallel-processing power of the M-series GPU completely idle. The one very important thing, is that the M-series chips have unified memory, which eliminates

the costly PCIe transfers that plague cuSPARSE on discrete GPU's. This creates a very unique opportunity for a GPU-optimized solver; we get the raw capabilities of the GPU, without many of the memory drawbacks.

Formats: CSR and BCSR

We focused on two storage formats: Compressed Sparse Row (CSR) and Blocked CSR (BCSR). CSR is our primary format; it is highly memory-efficient and it is ideal for general sparse matrices where the nonzero entries are evenly distributed. In BCSR, the nonzero elements are grouped up into dense (in our case $4\times4$) blocks, allowing us to make better use of the SIMD capabilities of the GPU. It also reduces the number of memory fetches, which are pretty costly.As a start, we chose to implement the CGD and BiCGSTAB iterative solvers first. They, compared to direct solvers such as SparseQR, are far easier to implement, and are well-suited for the parallelization given that they mainly require matrix-vector multiplications.

COO to CSR

This was the first major capability in the repository implemented. It was pretty difficult; we had to write a parallel radix sort. More importantly, it served as a (pretty brutal) introduction to writing code for GPU's. We packed the keys into a 64-bit integer, and sorted that, which thankfully, made life way easier. Hours were spent debugging garbage values appearing at the end; we found that it was all due to onesimd instruction. The converter

still needs optimization, but it's probably one of the more boring parts of the project.

CGD

CGD wasn't horrible to implement. We got it working pretty quickly, but the initial results were poor; it did worse than the PyTorch baseline at every test. This was suprising. Our SParse Matrix-Vector(spmv) kernels were fast; they ranged from $8$ to $200$-times faster than Apple Accelerate. CGD mainly uses spmv, so we were very shocked. We were forced to make many optimizations; some were easy, like reducing the number of times the GPU waited to sync up with the CPU. Others, such

as writing hyper-specific kernels, were more annoying. After some work, we finally optimized it enough to beat PyTorch, which uses Apple's Accelerate as a backend.

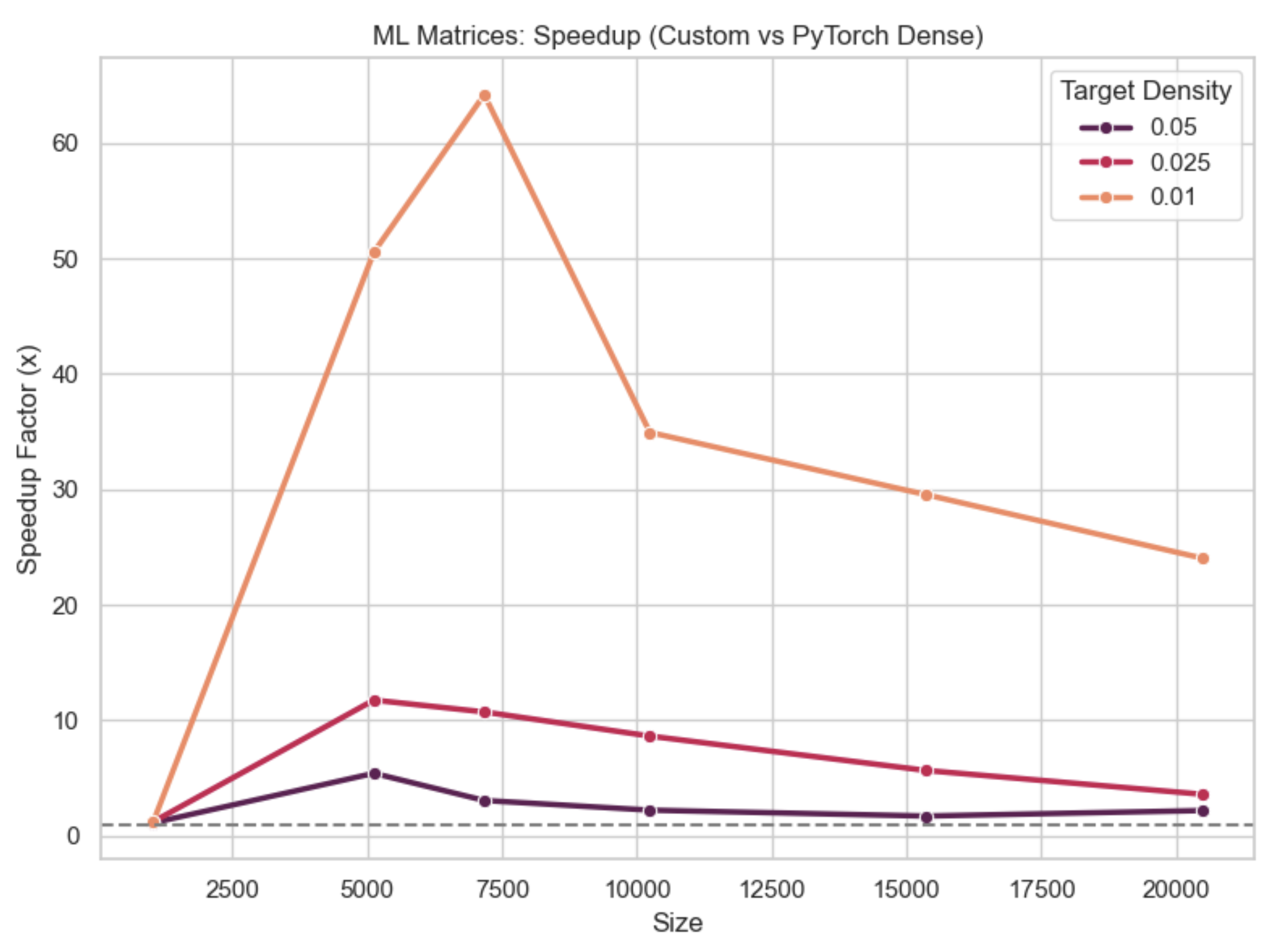

Our benchmarks consisted of matrices found in ML and physics, and we found the most signficant ($200$x) speedups in the physics matrices. In the ML matrices, at lower densities, our solver was $20$x faster; at higher densities, it was roughly $3$x faster.

Fig 1. CGD Performance on physics matrices

Fig 2. CGD Performance on ML matrices

After this part, I, at least, felt pretty invincible. We got a fast solver running! The next step, however, was BiCGSTAB, which definitely squashed that spirit.

BiCGSTAB

CGD is nice and all, but it only really works on symmetric positive-definite matrices. For a more general iterative solver, we turned to BiCGSTAB. This one required even more specialized kernels. We had fun naming some of the kernels here, one of them we namedf_upomega_upxr_laa, which has a meaning, but it could probably be articulated in a better way.

What was somewhat annoying here was the number of scalars that are needed to track; moreover, the atomic operations required some of those scalars to be zeroed out. But instead of writing another kernel, it's more

efficient to squeeze in the zeroing out in an existing kernel. With the lessons learned from CGD, we knew what optimizations to make ahead of the time; in fact, once it started working,

it was immediately faster than PyTorch.

The hard part was getting the damn thing to work in the first place. We'd finished the code and were excited; everything looked fine, and I, at least, expected a resounding success. Instead, we got

nan. This, like the COO to CSR conversion, took several hours

to debug; we found several critical bugs along the way. I don't think I've ever spent this much

time debugging one thing. Moreover, the compilation of the C++ took what felt like forever; it felt like complete ragebait.

We ran the solver on benchmarks similar to the CGD benchmarks, and we got some pretty good results.

Fig 3. BiCGSTAB (CSR) Performance

Fig 4. BiCGSTAB (BCSR) Timings

Fig 5. BiCGSTAB (BCSR) Speedup Factor

Reflection and Next Steps

MPSparse is far from complete; the biggest task remains ahead. Writing a sparse QR solver on the CPU looks hard enough, writing a GPU-accelerated one is probably harder. In the future, we also hope to write more adaptive kernels; this should give a substantial performance boost. That too, however, will be difficult. We also hope to expand support for BCSR. The final test is to compare this against Harry's 4090; if MPSparse can beat that, it would be amazing.Overall, this whole project has been pretty fun so far. It's definitely been a test of patience and will. It's taught me a lot about GPU/parallel programming and how you can squeeze out every single drop of performance from your computer by making the smallest optimizations. Once again, check out Harry's website and the repository on Github.

Sid